During the Warsaw Rising a transitory camp in Pruszków near Warsaw, known as Dulag 121, was created by Germans who were expelling Poles from every district they took over in Warsaw. The German authorities promised that the deportees would be provided with personal safety and decent conditions. These were empty promises. The Warsaw Rising Museum has a unique collection of photographs taken in Dulag 121. They are a poignant testimony of the plight the Poles found themselves in.

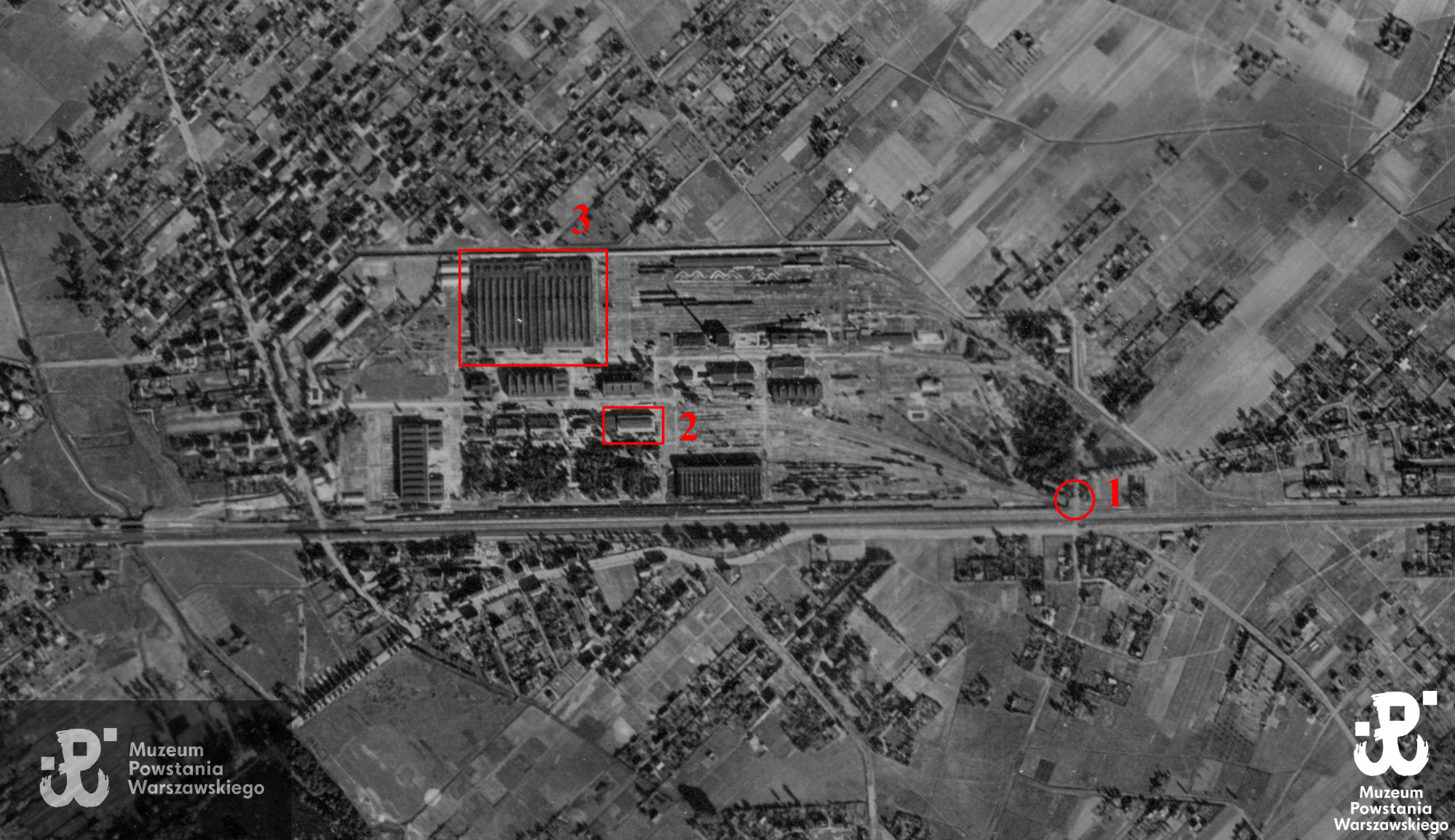

On August, 6 1944 (the sixth day of the Warsaw Rising), Germans established Durchgangslager 121 (Dulag 121) at the former Railway Repair Works in Pruszków. A 48 ha area was surrounded by a concrete wall with four gates. Nine huge repair halls were chosen and isolated with barbed wire. To understand the scale of ‘the project’ undertaken by the German authorities, please analyze an aerial photograph below taken on August,15 1944 where: 1 – refers to Gate 14; 2 – is the Repair Hall No.2; 3 – is the Repair Hall No.3.

A day later, the very first transport arrived. These were the Poles who survived the Wola Massacre. The next transports would arrive till 10 October 1944 when the last inhabitants of Warsaw’s City Centre district were brought to the camp. This date is considered to be the closing date for Dulag 121, the moment when the inhabitants of Warsaw would no longer be detained there after being expelled from their homes.

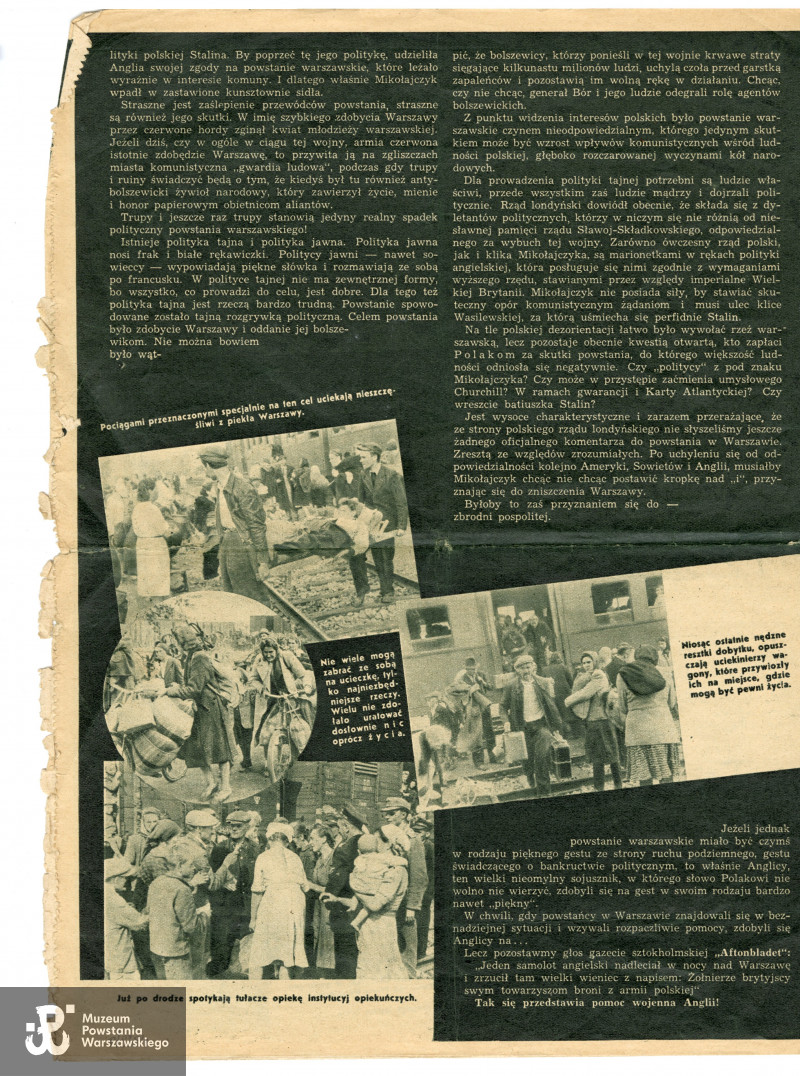

Everyday dozens of trains (freight cars and passenger coaches) would arrive at Gate 14 (Picture 1.). There were no platforms, so the deportees had to jump out to the ground. Analysing the photographs, one may observe that the height to reach the ground was substantial and German soldiers were not allowed to help the sick, wounded or the elderly. All the deportees had to carry their luggage that was usually too heavy and bulky. It was the only property they had left that was not consumed by the flames of the Warsaw Rising. German soldiers were shouting and exerted physical pressure on the poor people sent again into the unknown.

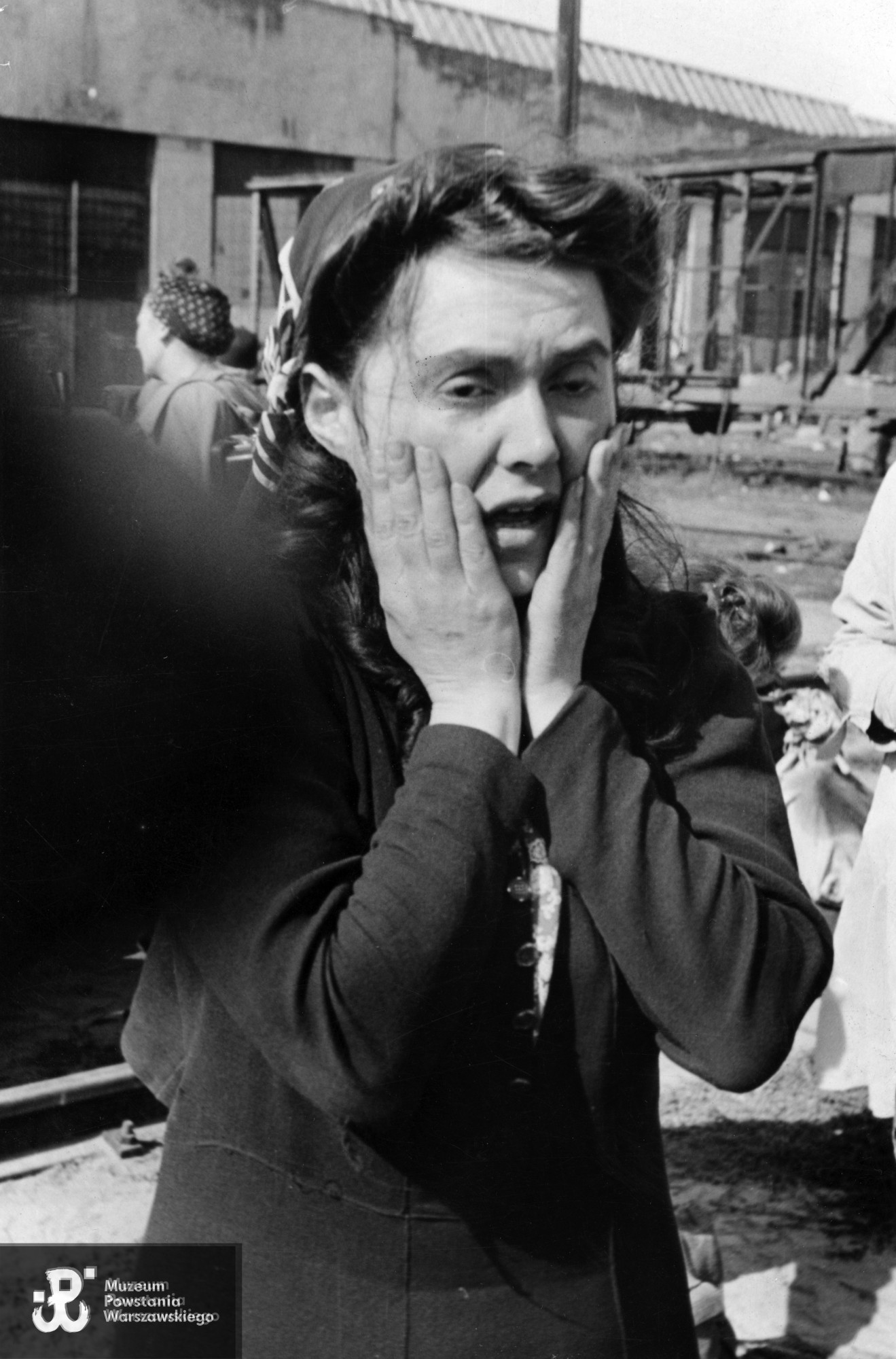

The remaining part of the deportees were sent to Hall No. 5 that served as ‘a transitory space’ where initial selection of those fit to be sent to forced labour took place. At that stage, it usually meant separation of family members, the procedure conducted by the German staff with wild animal fury, as recalled by the former Dulag 121 detainees. The photographs, where one may see scared faced women, reflect the horror of the situation. Thus, Dulag 121 has become the symbol of the tragic fate of Warsaw.

Generally, there were from a few to 40,000 people detained at the camp at once. At the peak, towards the end of September and the beginning of October, even more. The conditions were awful. The repair halls were without heating, and they were overcrowded and without proper air circulation. In each, there were ditches that had not been cleaned for two months. There was a shortage of straw mattresses or anything to sleep on. The deportees could find some rest usually only on the bare floor that was cold and wet, filled with human excrement, rubbish and rubble. The straw that covered the floor went quickly rotten, ‘moving’ with lice and other insects. That is why, despite cold weather, many detainees preferred to stay outside.

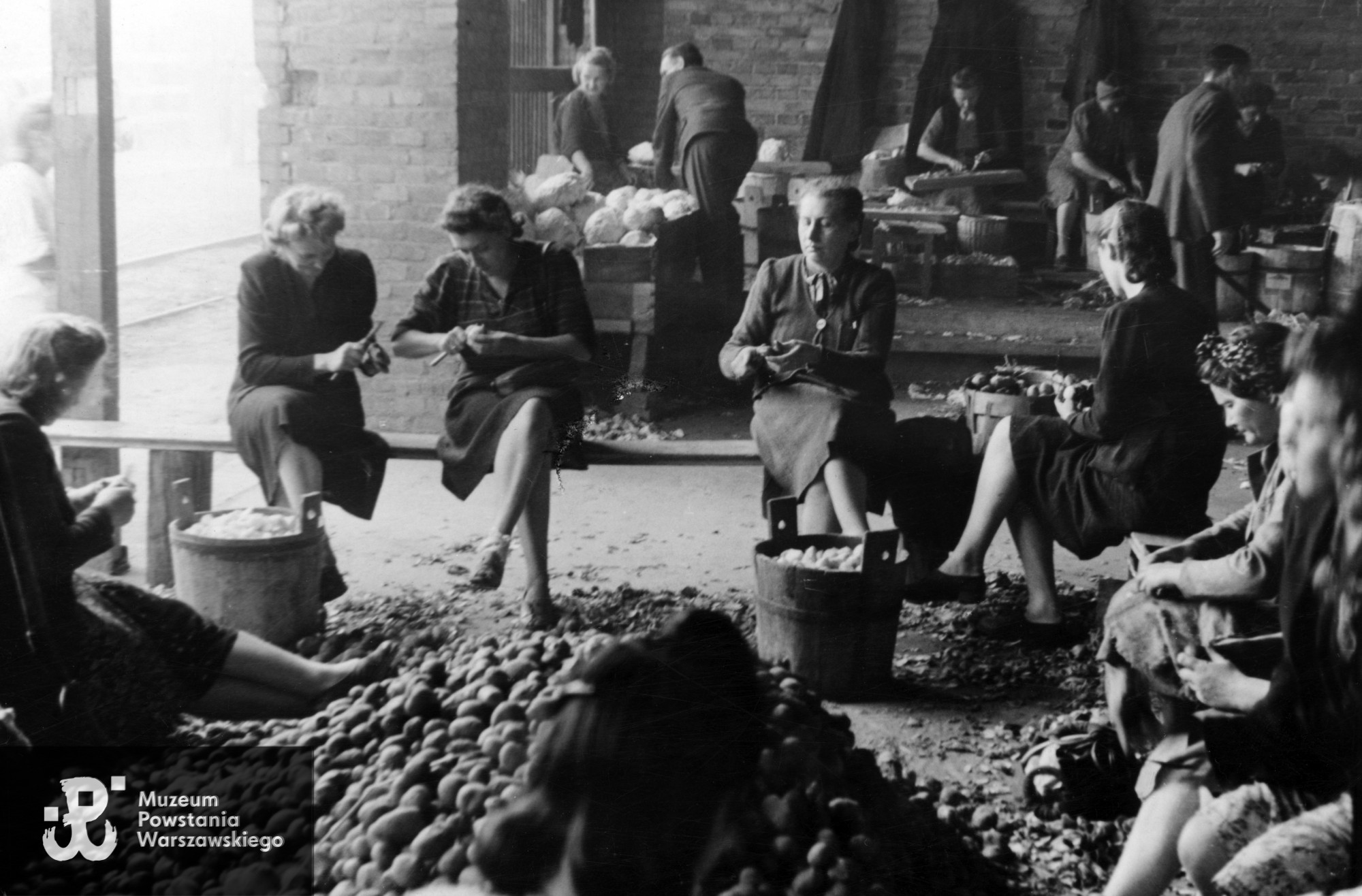

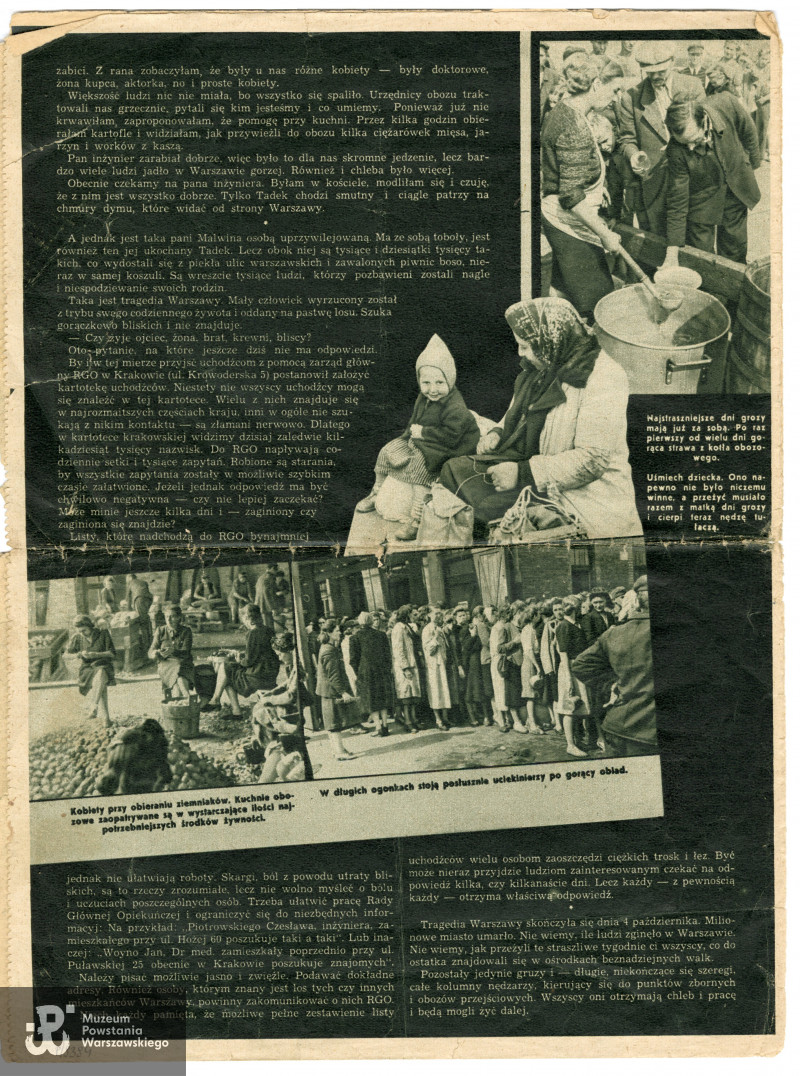

Every day the German authorities offered from 20,000 to 35,000 half-litre portions of a soup as a main meal. Additionally, the detainees would receive half-litre of coffee and 25 dag of bread for breakfast and supper. These were drastically meagre rations and the people were starving. Polish personnel, employed to prepare the food, did their best to expand the rations e.g., delivering milk for infants or distributing additional bread rations. Still, the situation was difficult. Initially, the food was given only to those who had their own dishes – one may discern in the photos the lucky ones who must have brought them with themselves.

One hundred German staff were employed in the camp. External Polish kitchen and medical personnel were allowed to work providing their help to the detained people. Luckily, without much restraint. There were dozens of medical doctors and almost 300 medics. They wore white coats and armbands with red cross. The Polish personnel did their best to save as many people as possible and protect them from being sent to forced labour or concentration camps.

The aid was also provided by nuns, mostly by Sisters of Charity as well as Benedictine Sisters from Pruszków. They were among all the deported people from Warsaw. They took care of the sick and offered help to many who later fled in disguise, wearing a nun’s or priest’s clothes.

Dulag 121 in Pruszków was a huge reservoir of forced labour for the German authorities. These who were unfit to work were considered useless and sent to different regions of the General Government and left without any help. Those who were ‘fit’ were sent to forced labour to the Third Reich.

When packing the people in the cars, no standards were met, and some people were suffocated due to extremely limited space. When sent into the unknown for a few days journey, they would often receive neither food, nor water. From time to time, Polish personnel managed to provide them with some food before departure into the unknown (see one of the photos below).

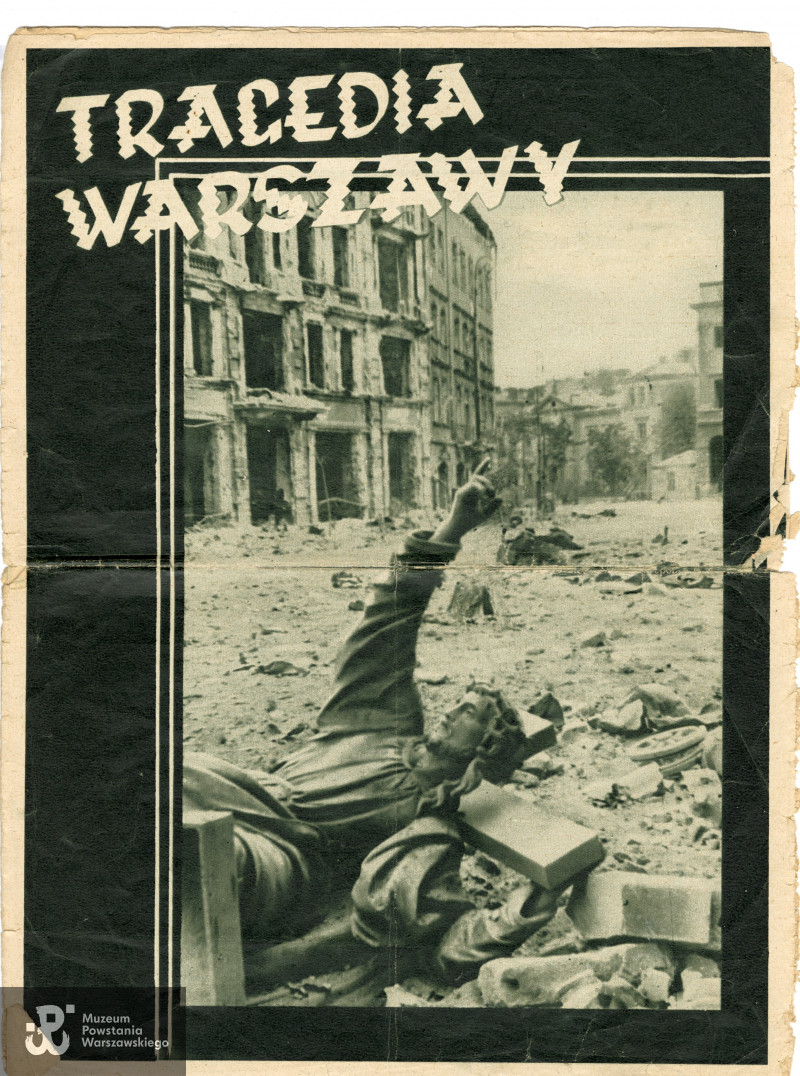

Most of the photographs were taken by Ewald Theuergarten, a German photographer, who was employed by one of the German newspapers. The photographs were published in a propaganda publication entitled “Tragedy of Warsaw” (Tragedia Warsawy). It promoted the view that the Polish commanders and participants of the Warsaw Rising are to be blamed for the misery of the civilians. There was no mention of the German responsibility for crimes committed in Warsaw. The footnotes were full of manipulation: “the people of Warsaw found hot meal, safe shelter and needed care in Dulag 121.”

The collection of German photographs taken in Dulag 121 is one of the examples of documentation created by Germans for their propaganda purposes. Germans were not aware that after WW2 it would become strong evidence of their barbarity.

This is the translation of an article written originally in Polish by Aleksandra Trzeciecka (Department of Iconography and Photography of the Warsaw Rising Museum).