Great battles aren’t always won by commanders. The pages of history are filled with examples of where universal virtues triumph over the soulless machinations of evil. An example of such moral victory is reflected in the life of Countess Maria Tarnowska. The Polish aristocrat who took part in the Warsaw Rising and saved tens of thousands of civilian lives…

Maria was born into an ancient princely family, the House of Swiatopelk-Czetwertynski. Her parents were Maria Wanda (née Uruski) (1853–1931) and Wlodzimierz (1837–1918). She was born on the 6th of July, 1880 in Milanów.

An article about Wlodzimierz Swiatopelk-Czetwertynski is already written, which means the focus should now be placed on the mother of the heroine. As it would later turn out, Maria not only inherited her mother’s name. Maria Uruska was called the Lady of the House (księżna milanowska), due to her incredible aptitude for handling economic affairs. In addition to how admirably she handled the management of her family's personal wealth, Maria Uruska was also involved in social as well as patriotic activities. Her home was a refuge for persecuted Uniates. In 1875, the Russians liquidated the Greek Catholic Church in the territory of the Congress Poland. Maria Uruska made travel between the borders of Galicia easier for Uniates, and she brought in Catholic priests who provided sacramental ministry to the persecuted. Her activities drew irritation from Tsarist authorities; her name would often appear in reports, highlighting her as opposing the system. Her activities did not only remain political in nature; she also involved herself in charitable endeavors, serving as the first chairwoman for the Catholic Union of Polish Women.

Later on, as the old proverb goes, the apple does not fall far from the tree; it is not surprising that her daughter would inherit these same qualities. From a young age, Maria Tarnowska was being prepared for humanitarian work. This started with the experience she gained from nursing courses, which had been organized by the Russian Red Cross.

Hrabina Maria Tarnowska ''Tygodnik Ilustrowany'' 1921 (Nr 1-13). Photo: Author Unknown/Public Domain

As was common for those times, girls born into aristocratic families such as Maria, would be married to a man that was much older than her. At 21 she was walking down the aisle to Count Adam Tarnowski (1866-1946), a man fourteen years her senior. Count Tarnowski was a secretary in the Austro-Hungarian embassy in Washington. Though much older than his new wife, Count Tarnowski did not evoke the impression of a responsible and mature older husband. Just five months before his wedding to Maria, Count Tarnowski found himself in a duel on the border of Monaco with an opponent from an equally illustrious family, the Tolstoys. Following the duel, Count Tarnowski had received a wound to the forearm. This incident, like the others that the Diplomat-Count found himself in the center of, was widely known and publicized back in the States. Even the New York Times had written about the Count’s exploits.

Even with the immature incidents and age difference, Maria liked her husband. "He was particularly attractive and a very charming man, as well as a wonderful dancer," she would later recall.

Due to her husband's diplomatic work, it often called for frequent travels and moving locations. Just in a single decade, the family had already lived in multiple major European cities, such as Paris, Dresden, Brussels, Madrid, and London, followed by Sofia. While in Bulgaria, Maria and her family found themselves in the midst of the First Balkan War (1912-1913). She involved herself in nurse work. A year later, in the Austro-Hungarian capital, she finished another nursing course. This experience would be valuable on the war fronts located on Polish territory, as ‘’The Great War’’ went into full effect. She worked as a nurse in the Lublin region and later in Cracow.

After Poland regained its independence, Maria involved herself with the Polish Red Cross Society. She was the co-organizer of a field hospital in Warsaw. After the outbreak of the Polish-Bolshevik War (1919-1921), she became a delegate for the Polish Red Cross Society, which was attached to the Polish Army. She headed a group of nurses from the 12th Podolian Uhlan Regiment, which at the time was commanded by the twenty-five-year-old Captain-Count Tadeusz Komorowski (1895-1966). In the first half of August 1920, she took command of medical units belonging to the 6th Cavalry Brigade. She was also entrusted with the role of commander of the front-lines unit of the Polish Red Cross.

As the dust settled on the battlefield, she was nominated for the position of Chief Nurse of the Polish Red Cross. She focused her efforts on educating nurses. Thanks to her initiative, nearly 300 health centers were established in rural areas by 1939. She was a tireless advocate for hygiene. Due to her efforts, a nurses’ home was created in the Polish Red Cross Society hospital, located at 6 Smolna Street in Warsaw, where a professional training program for nursing trainees was implemented.

International Conference of the Red Cross Societies in Prague in April 1933. Countess Maria Tarnowska- second from the right (standing). Photo Author Unknown/Photo from the collections National Digital Archive

International Conference of the Red Cross Societies in Prague in April 1933. Countess Maria Tarnowska- second from the right (standing). Photo Author Unknown/Photo from the collections National Digital Archive

Participants of the IX General Meeting Association of Sisters of Polish Red Cross in Warsaw in May 1933. In the front row, third from the left is Countess Maria Tarnowska. Photo: Author Unknown/ from the collection of the National Digital Archive

Participants of the IX General Meeting Association of Sisters of Polish Red Cross in Warsaw in May 1933. In the front row, third from the left is Countess Maria Tarnowska. Photo: Author Unknown/ from the collection of the National Digital Archive

In 1927, when at the Polish Red Cross Society’s base the Polish Red Cross was officially formed, Maria became a member of the board of management within the new organization. Ten years later, she became the head of the Polish Red Cross’s Sister Corpus, supported by the Ministry of Military Affairs. A year before the outbreak of World War II, Maria and her husband donated ten thousand dollars to the National Defense Fund. During the German occupation, in October of 1939, she became the vice president of the Management Board of the Polish Red Cross. She also directed the work of the Cracow branch of the Polish Red Cross.

She became involved in the activities of the Capital Social Assistance Committee. Furthermore, she was also a co-organizer of the Central Welfare Council (RGO). While living in Occupied Warsaw, Maria’s various connections, both familial and social, in addition to her holding senior roles in, among other things, the Polish Red Cross, led her to become involved in the underground movement. The Countess recounted, "During that period, charity work was the most important to me." Sometimes Maria was asked to create new documents for those who were in hiding. She hid conspiratorial materials in a hollow log that had been carefully fitted with a special lid. During emergencies (such as unexpected visits from “sad gentlemen’’), the log was taken to the kitchen and placed in a wooden box. The logs were so convincing that later identifying them proved to be difficult.

The Tarnowski couple provided the officer school of the Union of Armed Struggle, and later the Home Army, the first floor of their tenement house at 1b Pius XI Street (presently Piękna) in Warsaw. In the same building, on the second floor, lived Stanisław Jasiukowicz (1882-1946). He used false identities as the deputy of Government Delegation for Poland.

Photograph of building located near Pius XI 1B, property of the Tarnowski Family, Archive of the State in Warsaw

Photograph of building located near Pius XI 1B, property of the Tarnowski Family, Archive of the State in Warsaw

The Gestapo became interested in Maria following an investigation against Andrzej Jałowiecki (1911-1943), the director of the Warsaw branch of the Central Welfare Council (RGO). He was accused of mediating the transfer of funds intended for underground activities. In May of 1941, Jałowiecki gave Maria dollars, which were later taken by the president of the Polish Red Cross. In order to protect Jałowiecki, the countess admitted that the money was brought to her for the sole purpose of operating an orphanage. She was arrested and transported to Pawiak prison on the 10thNovember of 1942, where she was interrogated. In February of 1943, she was released after spending three months in Pawiak prison.

A month later, she became involved in conspiratorial activities. She was sworn in and given the pseudonym of Stanisława. She received the rank of lieutenant in the Home Army. Maria was entrusted with the position of Deputy Commander of the Women’s Military Service, making her responsible for training sanitary patrols. After the start of the Warsaw Rising, the messenger did not reach Maria. In the beginning stages of the Rising, the countess took care of organizing the civilians gathered on her block, advising on issues such as firefighting, first aid, organizing food supplies, etc. At a later period, she successfully reached the headquarters of the Women’s Military Service, using the city’s sewers as a passage. Once there, she was assigned to oversee all the paramedics located on Pius XI Street and to organize first aid points and field hospitals.

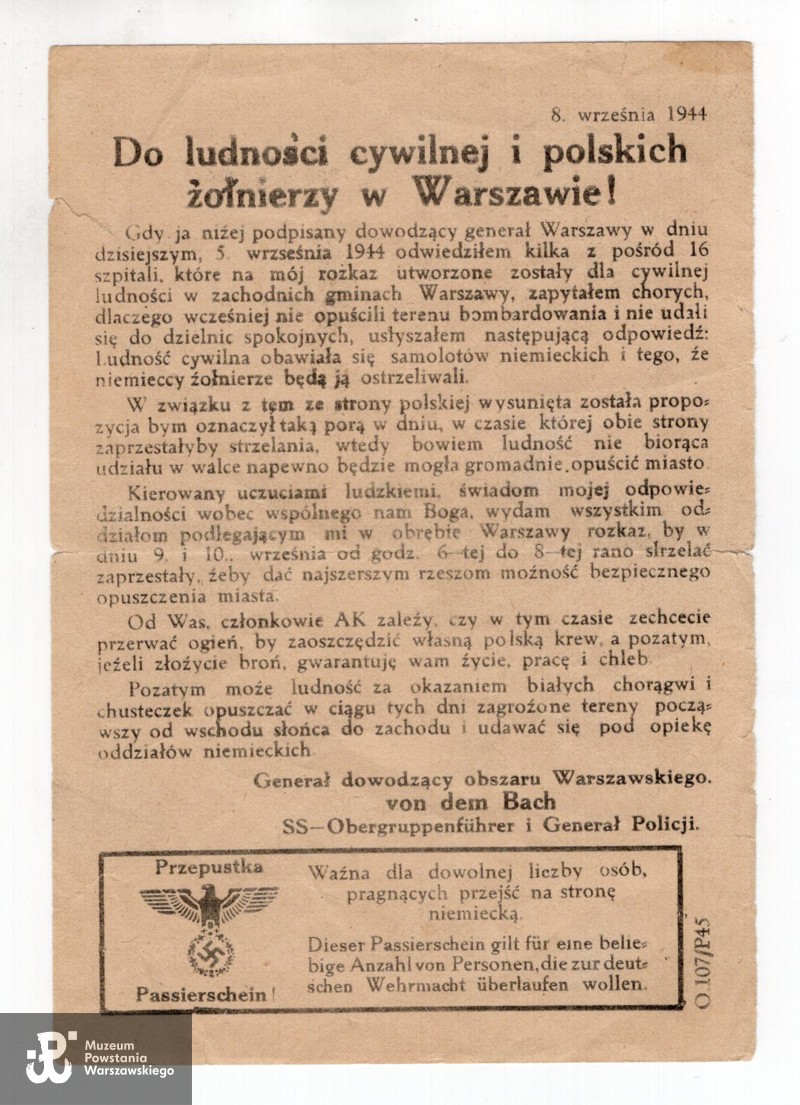

In the beginning of September, after resistance in the Old Town was suppressed, the German machine of destruction continued its violent strike on Powiśle District and the City Center. As a result of continuous artillery shelling of the area, as well as military defeats, there was a noticeable decline in morale among the population. People were starving, there was a lack of water, and basic everyday necessities were unavailable. The mortality of infants and children increased. Daily life was marked by monstrous stress, which was a direct cause of the military situation, coupled with the noise of artillery and collapsing houses. These feelings often became the catalyst for releasing pent-up emotions onto the insurgent authorities and soldiers. Calls were made for initiating capitulation talks, which were further encouraged by the Germans dropping leaflets in Polish on September 5th and 8th, urging civilians to leave the city.

Polish-language leaflet, dropped by Germans during the Warsaw Uprising on September 5 to 8, 1944. Photo from the archive of the Warsaw Rising Museum

Polish-language leaflet, dropped by Germans during the Warsaw Uprising on September 5 to 8, 1944. Photo from the archive of the Warsaw Rising Museum

Observing the mood of the civilian population, Countess Maria Tarnowska believed that chaos could not take over. She approached the Polish command with the initiative of starting negotiations with the Germans regarding the evacuation of the civilian population. She received permission to carry out negotiations from the commander of the Home Army, General Tadeusz ‘’Bor’’ Komorowski, whom she had been acquainted with since the Polish-Bolshevik War. Delegates of the Polish Red Cross- Countess Maria Tarnowska and Dr. Alfred Lewandowski- met on September 7th for negotiations with Major General Günther Rohr (1893-1966). Rohr's units had been actively pacifying the southern districts of Warsaw.

The Polish delegation headed for negotiation talks with the Germans. Photo. Autor Unknown/ from the Archive of the Warsaw Rising Museum

The Polish delegation headed for negotiation talks with the Germans. Photo. Autor Unknown/ from the Archive of the Warsaw Rising Museum

The Polish delegation before negotiation talks with the Germans; topic of the negotiations: the evacuation of the civilian population. Photo: Author Unknown/from the collection of Archive of the Warsaw Rising Museum

The Polish delegation before negotiation talks with the Germans; topic of the negotiations: the evacuation of the civilian population. Photo: Author Unknown/from the collection of Archive of the Warsaw Rising Museum

Countess Maria Tarnowska speaking with General major Güntherem Rohr. Photo: Author Unknown/Public Domain

Countess Maria Tarnowska speaking with General major Güntherem Rohr. Photo: Author Unknown/Public Domain

According to a report of one of the delegates of the Government Delegation for Poland, Edward Quirini, ‘’Stanislaw Kulesza’’ (1899-1954), the delegation spoke with SS-Obergruppenführer Erich von dem Bach (1899-1972), the commander of the German troops suppressing the Uprising. The dates, times, place, and evacuations of women with children and the elderly from the city were established. Civilians were permitted to leave the city from September 8th to the 10th, between 12 and 2 o’clock. The Germans directed them to a transition camp for displaced people in Pruszków (Dulag 121). Countess Tarnowska mentioned that about 10,000 people left Warsaw on the first day of evacuations, and the next day 4,000 people did. And on the last day a few hundred had left.

The Director of the Department of Internal Affairs in the Delegation of the Polish Government in the Country, Stefan Korbonski (1901-1989), estimated the group that left the capital came out to several tens of thousands of people. The limited interest of Warsaw residents in evacuation was mainly due to their distrust of Germans coupled with fear over the fate of their belongings once they would leave, essentially leaving their entire lives behind.

Photograph of Polish Red Cross Flag sewn on the night of 28 to 29 September 1944. Photo: Jarosław Maliniak/Warsaw Rising Museum

Photograph of Polish Red Cross Flag sewn on the night of 28 to 29 September 1944. Photo: Jarosław Maliniak/Warsaw Rising Museum

Shortly after being promoted to the rank of major (on September 23), the countess was once again involved with negotiations with the Germans regarding civilians. On the 29th of September, she became a part of the Polish Commission to investigate the conditions in the German transit camp for Polish civilians in Pruszków, as well as the location of Polish prisoners of war and hospitals in the suburbs of Warsaw. The Countess was also present in another commission, which met the following day to discuss the technical aspects of the evacuation of civilians with the German command. Her participation in these discussions was characterized by the German side’s protocol writer, Lt. G. von Jordan: "We had the impression that it was not the Poles who were capitulating, but we in front of the old countess." It also has to be mentioned that thanks to the efforts of the director of the Archives Department of the Warsaw Rising Museum, Dr. Jarosław Maliniak, the museum acquired a white-and-red flag made during the night of September 28-29 in 1944, which had accompanied the Polish Red Cross delegation during negotiations with the Germans for the evacuation of civilians.

Lt. Colonel Adam Borkiewicz, in his monumental monograph, reissued in 2018 by the Warsaw Rising Museum, wrote, citing German sources, that from October 1 to 7, 155,519 civilians were expelled from Warsaw. He also noted that this number is an underestimation and that significantly more people, probably around 200,000, had been expelled. Following the signing of the agreement to cease hostilities in Warsaw, which officially concluded the Warsaw Rising (October 2, 1944), the Representative of the Government Delegation for Poland , Deputy Prime Minister Jan Stanislaw Jankowski, ‘’Doktor’’ (1882-1945), entrusted Maria with a dangerous task. Because the Germans had promised not to search the countess and not place her in a transit camp, she was instructed to carry out of the city 500,000 dollars in small denominations from Warsaw and then deliver the large sum of money to a designated person in Podkowa Leśna. The sum entrusted was a heavy burden to the countess, who at the time was also caring for her sick 78-year-old husband.

To transport the money, the night before, a vest made to resemble a child’s vest was sewn from two towels and reinforced with strong tape. To avoid looking like a pregnant woman, which would be quite a peculiar sight considering the countess's age, she wore a heavy winter fur coat, even though it was around 13 degrees Celsius and the fur coat was far from comfortable attire. Despite the numerous difficulties, the money was safely delivered. After leaving Mazovia, the countess lived with her husband in Ojców in the Krakow-Częstochowa Jura. As part of her work for the Polish Red Cross, she cared for those returning from German concentration camps. In the new communist reality that Poland was in after the war, aristocrats, in addition to Home Army veterans, were treated with suspicion.

Maria was arrested by the Security Service under the suspicion of collaborating with the Germans and was detained for a month in the Public Security Office’s detention center in Olkusz. She was dismissed from the Polish Red Cross Authorities. In 1946, she left Poland and settled with her husband in Switzerland. Her husband would later die there in Lausanne. Then fate led her all the way to Brazil. Living in Rio de Janeiro, she was active in organizations linked with the Polish diaspora. In 1949, life dealt her a personal tragedy when her only son, Andrzej, died in a car accident. She returned to Warsaw in 1958; she lived near Poznanska Street. She died seven years later, on the 10th of July, 1965. She was buried in the family tomb of the Count Uruskis at the Old Powazki Cemetery (section Under the II Wall, row 1, place 32). Her merits were repeatedly honored with awards, including the Gold Cross of Merit with Swords (1944) and the Cross of Valour (1920). In 1923, she was the first Polish woman to receive the Florence Nightingale Medal—the highest award given by the International Committee of the Red Cross. In 2016, the President of Poland, Andrzej Duda, posthumously awarded Countess Maria Tarnowska with the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta for her outstanding contributions to Polish culture.

Author: Michał Wójciuk

Translated from Polish by Klaudia Szymonik