Frederic Chopin died in Paris after a long battle with tuberculosis on the 17th of October 1849. He wanted his heart to return to Warsaw, and after the composer’s death his heart was removed from his ribcage and placed in a glass jar which was filled with alcohol…

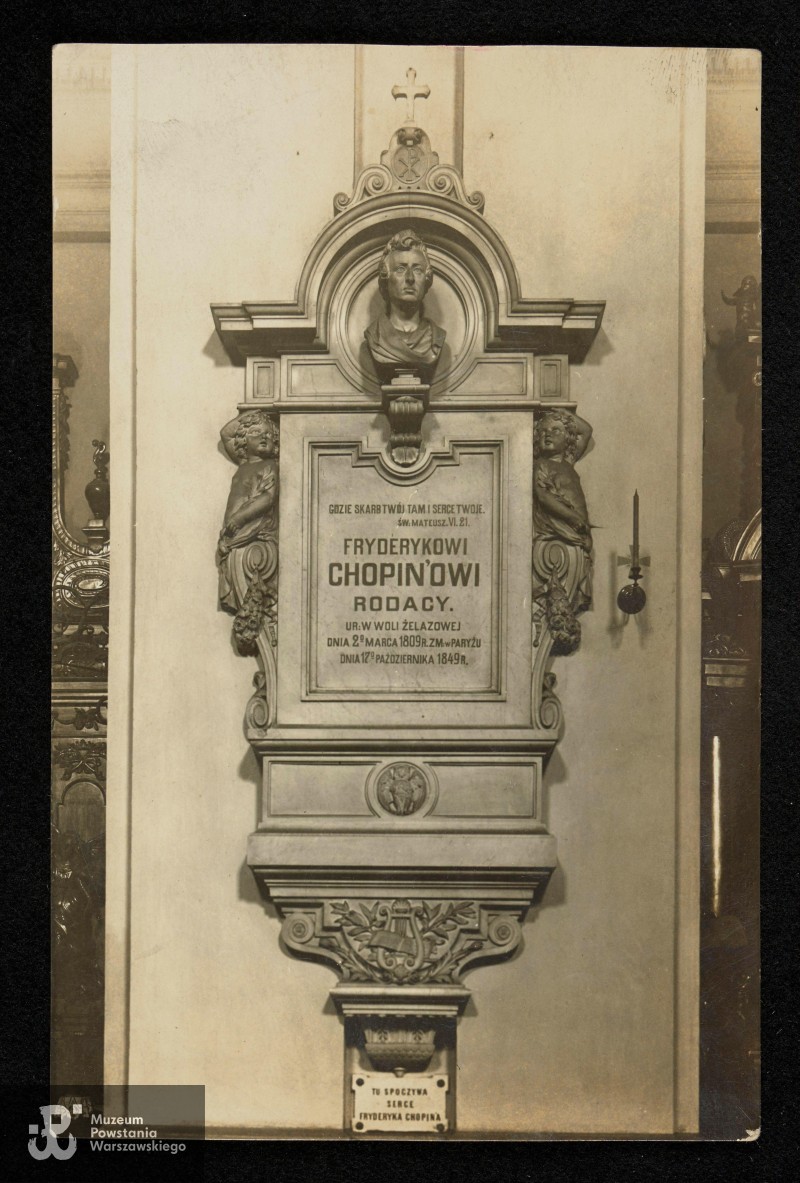

Chopin’s sister Ludwika Jędrzejewiczowa, secretly transported her brother’s heart to Warsaw, hiding the jar under her clothes, afraid that it could be confiscated. Fulfilling her brother’s final wish, Jędrzejewiczowa gave the heart to the Church of the Holy Cross, located on Krakowskie Przedmieście street, in Warsaw, Poland. It was the parish church of the Chopin family, the heart was kept there in secret in a folded box in the catacombs. In 1879, in secret from the Russian Tsarist authorities the heart was placed in one of the church pillars; the heart was placed in a double box, made of lead and wood, and then bricked up. A marble bust of Chopin was place by Leandro Marconi, accompanied by a plaque which read: “In memory of Frederic Chopin – Compariots”, along with a quote from the Gospel of St. Matthew ‘’For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also’’. The heart remained there until the start of the Warsaw Rising.

From the very beginning of the German occupation, Frederic Chopin was considered by German officials to be a dangerous symbol of Polish identity. Because of this reason one of the first statues which were targeted was the statue of Chopin, located in Łazienki Królewskie (by the sculptor Wacław Szymanowski), in May 1940 which on the orders of Governor General Hans Frank, was detonated and, in addition, cut up into pieces. At the same time, the Germans initiated a plan that would destroy all other copies of the monument throughout the General Government and the Wartheland. This resulted in the destruction of plaster casts and even a wooden copy which had been found in a museum in the Greater Poland Museum located in Poznań. The only memories of the composer that had been tolerated were the ones that indirectly referred to Chopin. In 1942, a guide was published by the Wermacht command in which there was a description of the Church of the Holy Cross along with brief mention of Chopin’s heart: ‘’A few steps away… You’ll find the Church of the Holy Cross, one of the most important centers in Warsaw. The facade of the church was built in the baroque style, characterized by its beautiful open staircase and a stone statue of Christ carrying the cross. The Church itself was built in the second half of 17th century, inspired by Il Gesù , the Roman Catholic church built originally in Rome, Italy, engaging many different architects who added their part at different times. Architect Jakub Fontana is mentioned as one of the creators of the facade. Statues of Saints Peter and Paul, which can be seen in front of the church, were created by Plersch. One of the columns of the church has the heart of Chopin composed in.”

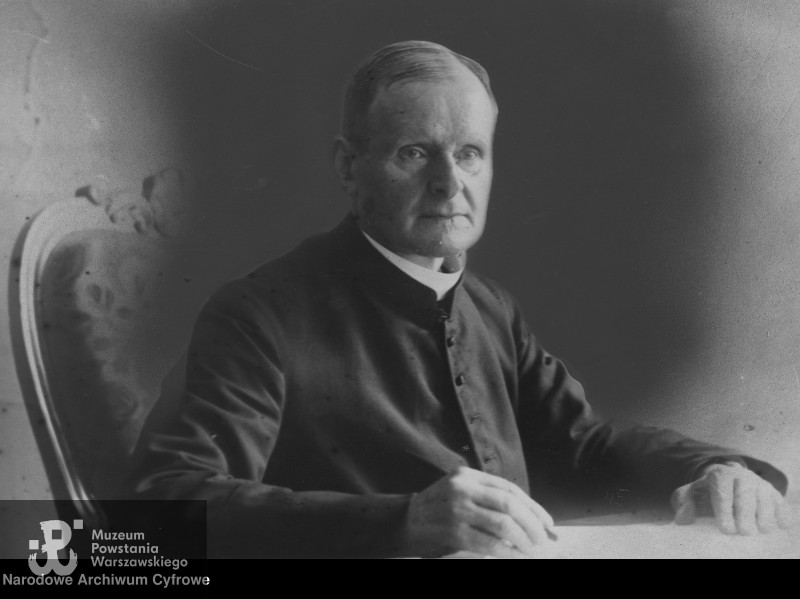

In the history of saving Chopin’s heart, a key role was played by Archbishop of Warsaw Antoni Szlagowski (1864-1956). He was a professor and rector of the University of Warsaw, and preacher; in 1944 he directed the Warsaw dioscese as chapter vicar: he became the titular archbishop in 1945. After the outbreak of the Warsaw Rising, he came into the orbit of interest of the German authorities. Half way through August 1944, German intelligence found out that Bishop Szlagowski was being held in an area under German control in the Pius XI Catholic House nicknamed ‘’Roma’’ on Nowogrodzka street. The messengers of SS Obergruppenführer Erich von dem Bach found him there and they were trying to convince the Bishop to coax the Warsaw Rising insurgents to capitulate, in response, Bishop Szlagowski said that ‘’He is not meant to partake in any situation of a political nature’’. The Germans however, were far from giving in easily and a couple days later they renewed their efforts, this time around counting on the Archbishop that he would give an announcement calling for women, children and the elderly to leave the city. Szlagowski would reject this request, his motivation being, that while leaving the city, women fell victim to rape. The Germans however responded with blaming the Ukrainian soldiers, in turn, the Germans assured the Archbishop that the Polish women would be guaranteed safety. Archbishop Szlagowski became concerned over where exactly the Germans were planning to evacuate Warsaw’s citizens, leading to the German’s taking the Archbishop along with priest Michalik to Pruszków transit camp on August 18th. Worried over the possibility that the Germans could have scripted the entire visit at the transit camp, Bishop Szlagowski demanded to be shown the entire camp, and not only the part of the camp where women were to be held. The Archbishop met with the displaced, and he saw first hand how they lived behind the barbed wire fence, he intervened against brutal selection for forced labour and the separation of families, he also asked for the release of the clergy from the camp. Unfortunately, the Germans continued to keep up appearances and did not accept the requests.

Archbishop Antoni Szlagowski in 1927 (NAC, public domain)

After the visit in the Dulag 121 in Pruszków on the 20th of August, captain Wilm Hosenfeld from the Wehrmacht Command of Warsaw, (known from the story of Władyslaw Szpilman, the author of the published diaries and letters ‘’I tried to save everyone’’) on the orders of General Rainer Stahel, Hosenfeld drove Szlagowski to the SS quarters in Sochaczew; the Archbishop was driven to the area in an armored vehicle, which awaken concern within Hosenfeld over the Archbishop’s health. Hosenfeld had met the Archbishop earlier, as he had guided Szlagowski through the destroyed fragments of Warsaw. By touring the ruins of the city, Szlagowski was to be influenced to become a mediator between the Germans and the Poles. In a direct conversation with von dem Bach, the Archbishop stated that he would not give the announcement of leaving the city, reasoning that the transit camp in Pruszków was far too small to house hundreds of thousands of displaced people. Von dem Bach was said to have agreed with the Archbishop’s arguments. Next the Archbishop was driven back to Warsaw, however reportedly due to heavy shooting by the gestapo of the ‘’Roma’’ building, the Archbishop was taken to the Hotel Bristol located on Krakowskie Przedmieście, where he stayed for a day. At the hotel he was to take part in an important meeting, but more about that as we go along.

Soon the Germans were heard from once again, demanding for the commanders of the rising to send two clergymen with the proposition of calling for a ceasefire. This request was fulfilled by archbishop - two priests volunteered: Priests Jan Pękala and Wacław Polasik. On the 28 of August they were able to travel through Marszałkowska street and they arrived to the Insurgent side, however until the end of the Warsaw Rising the Polish side did not respond to German demands. Germans still wanted to use the Archbishop in their plans: he was taken to the outskirts of Warsaw, where he gave a speech to Polish workers who were building trenches through forced labor. German propaganda immediately used this situation, manipulating it in a way that made it appear that Szlagowski supported the German war effort against the Bolsheviks.

Until the very end of August, von dem Bach warned the Archbishop, that he should leave Warsaw, as Hitler had given the order that the Warsaw Rising was to be suppressed and that Warsaw was to be leveled to the ground. At 4 o’clock in the morning, the Germans drove the Archbishop out of Warsaw, along with other clergy members, nuns and the elderly from Roma in a bus which was being escorted by two armoured vehicles to Milanówek, fulfilling the wish of Archbishop Szlagowski. Once in Milanówek, the Archbishop organized a temporary Warsaw Metropolitan Curia.

Photo taken during the Warsaw Rising. Archbishop Szlagowski among the civilians deported from Warsaw. Dulag 121. (Warsaw Rising Museum Collection)

According to Witold Konecki, during a short stay at the hotel Bristol, Archbishop Szlagowski met with Priest Alojzy Niedziela ‘’Alek’’ (Chaplain of the National Military Organization ‘’Harnaś’’ group) who served in the Holy Cross Church since 1943. Father Niedziela recounted the extraordinary visit to the church. From the beginning of the Rising the church came under the control of the Germans, treated as a strategic building with a machine gun installed in the tower. Two German chaplains were suppose to appear there (one was supposedly named Schulz or Schulze), they were to arrive and ask Father Niedziela for permission of extracting from the church the urn which contained the heart of Frederic Chopin. Previously a similar request was directed to Father Niedziela through Sister Klara, the Sister Superior of the Visitation Convent, which was under German control at the time. According to Father Niedziela, both German priests asked for discretion, they assured that they were ‘’Friends to the Poles and admirers of Chopin’s music’’, adding that they ‘’would do everything to save the urn and to hand it over to Polish church authorities’’. In a report from April 2000, Father Niedziela, mentioned he was in the ‘’Half destroyed church’’ when the German chaplain named Shulze approached him. Supposedly the German chaplain said ‘’Soon there will be fights breaking out over the Holy Cross Church. I am one of the many, like other Germans, who are avid admirers of Chopin’s music. If you would of course agree, we would like to take the relic, meaning the urn with the heart of the great composer, so that it would not be destroyed in the crossfire. We are ready to take it out of the urn, and save it from being destroyed and then transport it to a safe location.

The interior of the Church of the Holy Cross. Photo by Joachim Joachimczyk „Joachim” (Warsaw Rising Museum Collection)

The Church of the Holy Cross after WW2. Photo by Ryszard Witkowski

In 1995 a film directed by Piotr Szalszy entitled ‘’Chopin’s Heart’’, Priest Niedziela recounted a very important condition, which had influenced the priest that he would give the Germans Chopin’s heart, saving it from destruction - Shulz vel Schulze promised, that they would give the heart to church authorities. However, in the beginning this is not what happened – after Priest Alojzy Niedziela, Priest Czapla and Priest Chodzidło, Schulz vel Schulze took the heart from the church, and it ended up in German headquarters in the “House without corners” (Dom Bez Kantów) located opposite of the Visitation Sisters, where it was supposed to remain for a month. According to W. Konecki, the Archbishop Szlagowski was to find out about this, and after having listened to the story told to him by Father Niedziela, he decided to agree to the Germans’ proposal. However, Father Niedziela does not agree with this version of events, he recounted the Archbishop’s role, and he highlighted the entire situation as a personal initiative of all the priests. What also does not add up, is the chronology of all the events, Bishop Szlagowski could have had an audience with Father Niedziela around the 21 of August, during which, as recounted by Father Niedziela, the German chaplain was supposed to visit him on the 8th, 9th or 10th of August. Meanwhile Witold Koniecki suggested that the German chaplains were carrying out the orders of the SS Obergruppenführer von dem Bach, suggesting at the same time, that just after receiving permission from Priest Niedziela, the Germans took out the urn and took it to the ‘’House without Corners’’ building. As written by W. Konecki: ‘’It was plain to see, that the Germans wanted to organize a propaganda spectacle, around the urn that carried Chopin’s heart, this was supposed to soften the opinion over German war crime activities against the Insurgents, civilians and the city of Warsaw. As reported by Father Niedziela in 1995, he spent years clarifying various versions of the circumstances under which Chopin’s heart was taken from the Church of the Holy Cross, notably among others in the ‘’Evening Express’’, emphasizing the role of the Wehrmacht chaplain, contradicting the accounts which had suggested that the heart had been taken by the insurgents or by German soldiers from the ruins of the church. As he mentioned, during Poland Communist period, the story of German chaplains saving the heart was not well received by Communist authorities, and it even led to interrogations of the priest by the Security Office regarding this matter.

During the Rising, Schulz/Schulze was to have contacted the Polish priests once again, as was shown in Piotr Szalszy’s film from 1995. Priest Chodzidło and Priest Czapla, unfortunately did not reveal how and through whose intermediary, did Schulze manage to reach the priests and when exactly did this take place. According to the narrator of the film, Schulze was to be driven by a sense of guilt stemming from the enormous suffering of the residents of Warsaw. Shulze, referred to as a ‘’division chaplain’’, was then in Żyrardów, and it was the two priests mentioned above who were supposed to go with him. Schulze, revealed that the Germans had just blown up the bell tower of the Church of the Holy Cross (which meant it had to be during the fighting for control over the church between the 1st and 6ht of September, or later on when the church was already in German hands), and he was afraid they would demolish the rest of the church. The German Chaplain then asked Priest Chodzidło and Czapla, if the church doesn’t have anything else that could be saved. The priests admitted that in the sacristy there was supposed to be a locked safe containing hidden liturgical vessels. The priests provided Schulz with detailed plans of the church, and he promised that he would save these vessels. Schulze/Schulz came to the church with Polish workers and another German, who titled himself as ‘’Hauptmann Scheue lub Scheu’’ (Captain of the Wermacht), together they opened the safe and transported the items to Father Chodzidło in Grodzisk Mazowiecki. Years later, the priests expressed their gratitude to Schulze for this extraordinary action.

The next mention of Schulze comes from the 12th of September of 1944. According to the Sisters of Charity, specifically Sister Anna Jurczak’s account in the 1995 film, Schulze come to the Sisters of Charity on Tamka street to inform them of the fate of those deported to Pruszków. Mother Klaudia, the superior of the Visitationists, described what happened in the Visitationist convent during the Rising. She remembered Schulze as a great lover of Poles, eager to salvage what he could from Warsaw churches. In 1967, she wrote about Schulze in her account (I thank Michał Wójciuk for introducing me to this text): “Military authorities ordered for the monastery to evacuate, giving them a deadline to the 10th of October. That day in the evening an ambulance took our ill nuns to the hospital located in the Wola district, the rest of the nuns were given permission to remain until the 15th of October, so that they would be able to pack up the church’s antique apparatus, paintings, books etc. Such turn of events was thanks to the regiment which was stationing around us, the regiment consisted of Rhineland Catholics, who found the situation as painful as we did. Many church items were saved by chaplain priest Jan Schultze, taking out of burned and abandoned churches liturgical vessels and apparatus etc.”

In an interview from 2000, priest Alojzy Niedziela said that priest Schulze was killed in the outskirts of Warsaw during a Soviet offensive in the winter of 1945. This was mentioned in a 46 minute film by P. Szalszy, which also presented a photo portrait of Priest Shulze, signed as the original ‘’Pfarrer Schulze’’. Unfortunately the source of this photo remains unknown.

In the meantime, on the 23 of August, 1944, a battle for the church broke out. As a result the Insurgents were able to gain control over the church, and held it up until the 6th of September, when the Germans bombarded from the earth and the sky the entire religious structure. The soldiers of the Home Army from the Battalion ‘’Gustaw-Harnaś’’, who gained control over the church and a nearby police station, already on the 23 of August, noticed a hole in one of the pillars, where the urn was suppose to be. As Kazimierz Radwański ‘’Kazik’’ had recalled: ‘’I always was interested in the urn with Chopin’s heart in it. The Urn was and is to this day in the second pillar on the northern side of the church, separating the main nave from the side nave. I noticed that the bricks were taken out and the urn with Chopin’s heart was missing.’’ Kazimierz Radwański in the later part of the interview relies on the facts about Chopin’s heart, however revealing that his knowledge about the story, is thanks to Priest Niedziela from the 1990s. At the same time, it is worth asking the question, what were the soldiers of the Home Army told. According to paramedic Jadwiga Kozłowska ‘’Iga’’ of the Gustaw - Harnaś Battalion, when a fire broke out in the church, priest Niedziela himself took out the heart and buried it under a tree, and later he uncovered it and placed it back where it was originally. She added on: ‘’but during Communist times you could not talk about this, because the officially sentiment was what? A priest would actually do that?’’

The topic appeared in the Insurgent press on the 28 of August, written in the ‘’Demokrat’’ gazette: In response to rumors saying that during the fire in the Church of the Holy Cross the urns with Chopin’s heart and Reymont sustained damage, we have received a confirmation from a credible source that both urns survived. On the 29th of August the Information Bulletin reassured that: “After the Germans had set fire to the Church of the Holy Cross, the altar of Saint Roch and the Holiest Sacrement went up in flames completely. The Urn with Chopin’s heart and the Urn with Władysław Reymont’s heart, as well as all liturgical items survived.” In the very beginning of September, Kazimierz Moczarski, a Warsaw Insurgent serving in the Home Army’s Bureau of Information and Propaganda, and the later author of ‘’Conversations with an Executioner’’ wrote an enigmatic note: ‘’We are keeping safe the Heart of Chopin, which was carried out of the Church of the Holy Cross’’. It is suggested then, that the urn with the heart of Chopin as well as the urn with Władysław Reymont’s heart found within the church, were still presently kept in the church. This of course was not true, at least when it came to Chopin’s heart, however at that point no one was aware of that (small disgression- the information surrounding the fate of the urn with Władyslaw Reymont’s heart during the Warsaw Rising is unclear).

Epitaph in memory of Frederic Chopin inside the Church of the Holy Cross in Warsaw. Photo taken before 1939. Source: Polona

According to W. Konecki, Erich von dem Bach had decided to use this war bounty in the form of Chopin’s heart and return it to church officials. For this very reason, on the 9th of September, two officers, who had convinced the archbishop to leave Warsaw, had the goal of taking away the heart. They supposedly say, ’Our soldiers found Chopin’s heart in the ruins of the church. We know how great and how important this memento is to the Poles. We decided to save it, and we wish to give Chopin’s heart back to the most worthy hands of the Archbishop of Warsaw. In the opinion of a witness, priest Stanisław Markowski, they falsely conveyed to him at the time that German soldiers allegedly found an urn with Chopin’s heart in the ruins of the demolished Church of the Holy Cross. As Andrzej Pettyn writes in the article ‘’Chopin in Milanówek,’’ Szlagowski left the rectory of the church of St. Jadwiga and, along with priest Jan Michalski and the deputy pastor of the parish in Milanówek, priest doctor Jerzy Modzelewski, travelled with the Germans by car to Warsaw. The trip was described by writer and Warsaw Insurgent Stanisław Podlewski in an article entitled ‘’The Relic of Saint Chopin’’ (published in the journal ‘’Za i Przeciw’’ (16. 09. 1973): The clergy during the entirety of the trip worried that there would be a trick. The car drove up to Wolska 84/86 Street, where in the office and warehouse buildings of the company ‘’Społem’’ was the Räumungsstab der Ziwilverwaltung (Evacuation Staff of the Civil Administration), where goods stolen in Warsaw were being brought. In front of the building, German honour guards presented arms, and a red flag with a black swastika hung on the walls. The officers led the archbishop and the priests to a room on the first floor. The room was to be ‘’flooded with lights from spotlights’’ and cameras.

Suddenly, in a moment when the archbishop was supposed to accept the urn with the heart, all of a sudden there was a technical malfunction, the reflectors shut down, and the electricians present were unable to fix the failure on the spot. Priest Szlagowski then reportedly said to the priests, "Thank God, this time the barbarians will not be able to use this moment for their propaganda." Priest Waldemar Wojdecki, author of the book Archbishop Antoni Szlagowski: Preacher of Warsaw, stopped at the point, stating that the film was not made. However, from 1995, we know that a small fragment of film had been preserved (information I got thanks to Andrzej Zawistowski) showcasing a scene that shows the heart being given over to Bishop Szlagowski by SS-Obergruppenführer Erich von dem Bach himself. The fragment preserved in the archives of the Studio of Documental and Popular Films was used in the documentary film ‘’Chopin’s Heart’’ (Fokus T.V., 11.07. 2018) - the aforementioned fragment is found at 41 min. 33 seconds- 42 min. 18 seconds (Available: 5.03.2025)

A frame from the film that was shot by Germans. Source: film Piotra Szalszy „Serce Chopina”, (Accessed on 10.03.2025).

While still in the hall one of the higher-ranking officers of von dem Bach headquarters had said to Szlagowski: ’During this war the great Reich has always done everything that was in her power to protect from annihilation and destruction the most valuable cultural treasures of universal culture for future generations. The German soldier in the East defends the old Christian culture from annihilation and barbarism… Fulfilling the order of the Obergruppenführer and Police General von dem Bach, I am delivering to His Excellency the Archbishop an urn with Chopin’s heart, found by our soldiers”. Then he handed the archbishop an oak urn shaped like a prism and raised his hand in the Hitler salute. The archbishop in this surreal moment timidly expressed his thanks.

However, this description was cited by S. Podlewski and W. Konecki; this, however, is at odds with the picture that we observe, which is this moment, which is only 1.5 minutes long, where the Heart is handed over in the yard of the warehouse ‘’Społem’’ (the exact localization was investigated and found by Michał Pałgan, the creator of the historical Facebook fan page dedicated to the history of Warsaw’s Wola district titled "I am from Wola." (Post from 19.11.2019) as well as well-know Warsaw specialist Professor Zygmunt Walkowski, who presented a way in which to identify the area with the help of photos taken on board from an aircraft. During a lecture by Professor Marek Bykowski in DSH on Karowa Street (20.02.2025) the origins of this short propaganda film without sound remain unknown. The director of ‘’Chopin’s Heart’’ Piotr Szalszy, who was filming for Austrian television, in a later interview said that it was an unpublished material. He found also a never published Nazi German propaganda film, showcasing a moment of ‘’the noble’’ handing over of the urn (with the Chopin’s heart encased inside) to Archbishop Antoni Szlagowski by General Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski - the Executioner of Warsaw, who in a moment would burn down the entire city. (citation: Monika Patryk, ‘’Dilettante or connoisseur - an interview with Piotr Szalszy). Kazimierz Gierzod (1936- 2018) rector of the Fryderyk Chopin University of Music in Warsaw, claimed to have a copy of the German weekly chronicle ‘’Deutsche Wochenschau’’ dedicated to the Warsaw Rising (the topic appears in a total of five episodes), nor in its Polish-language version ‘’Tygodnik Dźwiękowy Generalnej Guberni’’ (Translation: The Weekly Sound Journal of the General Governement). At the same time, due to its clearly working material, it seems doubtful that it would have made it to cinemas. However, there is a version of this story according to which Germans did indeed broadcast the scene. According to the memoirs of Father Canon Stanisław Markowski, the scene of the heart being handed over appeared precisely in the short version before films in the General Governement cinemas. The sister of Father Jerzy Modzelewski, Lucyna, after having left Warsaw following the Rising, stayed in Częstochowa and went to the cinema there. Suddenly, that propaganda film appeared on the screen, in which she recognized her brother, shouting: ‘’Jurek!’’, which created a commotion among the others gathered in the movie theatre. Does this mean, that a film was indeed created with sound from the scene where Archbishop Szlagowski is receiving Chopin’s heart? There is no answer to this question.

The preserved fragment of the film contains three scenes: the Archbishop in a hat, shielding Father Michalski, with Father Modzelewski on his right, von dem Bach standing facing him, facing the camera and with the Wehrmacht officer standing sideways to the scene, and another officer in a cap behind von dem Bach. In the background stand a German soldier with a slung rife, next to him a casual looking officer without a hat, another officer in uniform and additional soldiers and officers are barely visible, obscured by parts of the building or even out of frame. The short is exceptionally unprofessional, positioned at an angle, showing part of a work building, not focusing on anything, and on top of that, the main characters of the scene are too far away. The next shot, a close-up, at some point the image darkens and immediately brightens again - showing the scene of the box being handed into the archbishop’s hands by von dem Bach. Bach is speaking for a short while, slowly he opens the box/chest, in that moment the priests take off their hats, from behind come up Priest Modzelewski, Szlagowski turns, to hand over the chest to someone. From behind Bach comes an officer with another chest, which he proceeds to open- there the film cuts suddenly. It is hard to figure out who actually at that moment is holding Chopin’s Heart. The Germans in the background (in all: eight German officers in addition to Bach appear in the film) though not regularly. The last scene is a close-up of Bach’s profile, who whole speaking takes a step backwards, and proceeds to do a Nazi German salute, not too long he turns and his face takes on a satisfied expression from the entire scene, he also squints his eyes, as of the sun was bothering him. Then the camera does a quick close-up of the box - chest with the heart with a rather unreadable subtitle, however one is able to make out the words ‘’Frederic Chopin’’. Finally for a moment, the camera shows a close-up of Archbishop’s Szlagowski’s face who is having a twisted grimace.

The scene gives off the impression of a working shot, which was resulted in a failed take, that would need to be refilmed and restaged. The background of the scene was irrelevant, the framing, the carelessness of the whole situation indicates that they were simply practicing the choreography of the main participants’ movements on the scene, perhaps estimating the timing of its individual elements. In the film, it is possible to recognize (probably) two significant Wehrmacht officers, more on the later. According to K. Gierżod, the Germans were still doing reshoots in Milanówek at the parish of St. Jadwiga. According to Stanisław Podlewski after the return to Milanówek on the 9th of September at the parish a protocol was formulated from this whole moment which had the following contents: “Day the 9th of September 1944, at 5:30 in the afternoon near Wolska street, in the building ‘’Społem’’ the German General von dem Bach, in the presence of the Governor of Warsaw Fischer and the Vice-Governor Keller as well as Priest Jerzy Modzelewski and priest Karol Milik, the heart of Frederic Chopin was personally handed over to His Excellency Archbishop Szlagowski, who oversees the Archdiocese of Warsaw. Frederic Chopin’s heart was located within a glass vessel inside a black case and wooden box. The cassette with the heart originates from the Church of the Holy Cross in Warsaw. It was signed by Archbishop Szlagowski, Priest and doctor Jerzy Modzelewski.” The document is peculiar because it contains contradictory information from the Polish side (for example the fact that Fr. Michalski or Fr. Milik were present. The information given by the German side is also questionable (Governor Ludwig Fischer is not visible in the photo, while other individuals are omitted). The Archbishop was concerned about von dem Bach’s intentions, so as a precaution, he moved the urn to Professor Antoniewicz’s house in Milanówek on Sosnowa street. Only after some time he retrieved it and moved it back to the parish. There, the urn stood on the piano in the Archbishop’s private chapel until October 17th, 1945, when it was ceremoniously returned back to Warsaw.

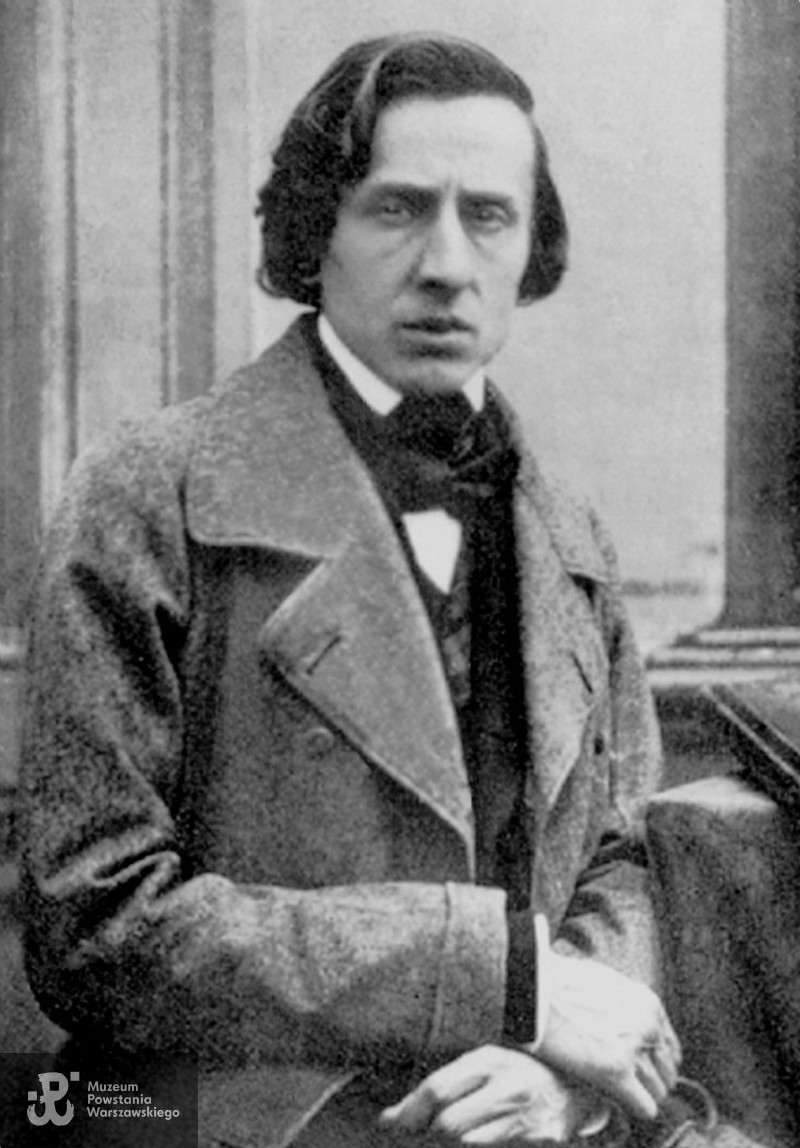

Frederic Chopin in 1849. Photo by Louis-Auguste Bisson

After 1945, many unverified versions surrounded the fate of Chopin’s heart. They materialized from disinformation, which had been consciously used during the fighting. The insurgent command was not in favor of revealing the conversations of Polish priests and the German chaplains, while the Germans counted on the propaganda equally, which could be manipulated for their benefit. Investigating how and in what way the story of how the heart appeared in German propaganda films, besides the mentioned film (the topic was also present, especially in the Polish press titles that were taken over by the Germans in WW2), is a very interesting topic. There was a belief that during the battles, the urn with the heart was found in the ruins of the Church of the Holy Cross. Either German soldiers or, under unexplained circumstances, anonymous insurgents carried the urn with the heart out. Thanks to Priest Alojzy Niedziela, the account (though not the full version) of the events formed for itself a road. The first time in history the handing over of Chopin’s heart, which had already been mentioned, was presented by Stanisław Podlewski. A sensational series of reportages based on conversations with Nazi German dignitaries by Krzysztof Kąkolewski (1930-2015), a journalist and publicist, entitled ‘’How are you doing, sir?’’ (1st ed., Warsaw 1975) was a revelation. In 1973, Kąkolewski interviewed Heinrich ‘’Heinz’’ Reinefarth, the “butcher” of Warsaw’s Wola district, who was featured in the aforementioned book. At one point Reinefarth mentioned Chopin’s heart: “I had an attack of dysentery. I was lying in my quarters. An officer reported that his unit had captured a church after hours of fighting, where they had found some kind of relic. The officer placed a leather case in front of my bed. The case had a surname on a small plaque. I ordered it to be placed on the wardrobe. The Archbishop of Warsaw was outside the capital, besieged by battles, and von dem Bach had made contact with him. However, the archbishop said that no saint with that surname exists. Then I proceeded to open the case. It turned out that the surname on the plaque belonged to the manufacturer, and it was an advertisement for the company. The name on the vessel read ‘’Chopin.’’ In a flash, because I have always been passionate about music and play music myself, I remembered Chopin’s testament: ‘’Body in Paris, heart in Warsaw.’’ Chopin remained a Pole at heart.” (quoted after Krzysztof Kąkolewski, ‘’General Reinefarth, you know your nickname,’’ in Literatura, ‘’no. 22, May 31, 1973). Reinefarth’s alleged involvement in this story took on a life of its own and appeared in Mieczyslaw Czuma and Leszek Mazan’s book “Poczet serc polskich” (Krakow 2005)), and in Ewa Solińska’s publication, Chopin’s Secrets (Warsaw 2012). In the above-mentioned version, there is not a single truthful word, and it actually showcases that following the end of World War II, multiple German Nazis tried to skew and manipulate public opinion in their made-up, still very much alive propaganda of the Third Reich, especially in reference to the Warsaw Rising. Their attempts were also to soften their image, an example being the supposed help in saving one of Poland’s most important national treasures.

Marek Bykowski, the perennial Chancellor of the Chopin University of Music, someone well-versed in the life and work of the composer, during a lecture at DSH on 20th February 2025, said, '’A native Varsovian… Chopin’s heart,’’ he hypothesized that the Germans were relieved to get rid of Chopin’s heart, which they had taken out of the church; next, however, they had no idea what to do with it. The question was how to use the heart in such a way that would bring them the most benefit. The nonchalant attitude of von dem Bach, showcased in the film, in reality did not give any impression that he had in any way involved himself in the entire situation. However, he still agreed to appear in the film, as in the moment he believed that the final act of the fall of the Warsaw Rising was playing out. However, a very important question does appear: with certainty, did Bach that day (the 9th of September) need to be in the military staff, or on the front, or anywhere else of importance rather than on the backlot of a warehouse of "Społem"? Next to him in the movie, which was filmed on Wolska Street, appear other important Wehrmacht officers. The man in a military cap with a scar on his face, at one point, is coming closer with a box on the urn; this is most likely General Helmut Max Staedtke (1905-1974), the Chief of Staff of the 9th Army, which participated in the suppression of the Rising in cooperation with von dem Bach. Staedtke, as a veteran of the Eastern Front, was an ambitious officer, wanting to rehabilitate his 9th Army in the eyes of Hitler, which had been defeated by the Soviets in Belarus in 1944.

His task was to ensure the swiftest capitulation of the Warsaw Rising, which Hitler eagerly waited for. Not only is the presence of Staedtke not the only puzzling factor, but in the background one can see an officer in a general’s uniform. It is hard to make him out on the film; however, it is most likely it was Lieutenant Hans Wiheln Schirmer (1888-1955), the successor of General Rainer Stahel as the War Commander of Warsaw. That is, in the warehouses of the ‘’Społem’’ company on September 9, 1944, three key German commanders who were responsible for suppressing the Warsaw Rising were present at the same time (missing was the commander of the 9th Army, General of the Panzer Corps Nikolaus von Vormann, who was soon to bid farewell to his post). The question that remains unanswered is why the ceremony of giving over Chopin’s heart in this moment was more important than commanding an operation against the ongoing rising. The only answer to this question is the date - the 9th of September 1944, otherwise known as the second day of the capitulation negotiations with the insurgent command.

84/86 Wolska Street, Warsaw, where "Społem" warehouses used to be located. The area where the film was shot. Photos by P. Brudek, March 2025

The Germans expected a lot to come out of the negotiations, which at that very moment had been ongoing between the envoys of the Home Army Headquarters, Lieutenant Colonel Franciszek Herman "Bogusławski" and Captain Alfred Korczyński, and General Heinz Rohr, who represented Erich von dem Bach. During the negotiations, the Poles demanded further evacuation of civilians and the seriously wounded Polish soldiers. Topic of discussion was also: the transfer of German soldiers who became prisoners of war and were being held by the insurgents. General Rohr moved the conversation on to the fundamental matter, which was the talks of capitulation of the Rising. The Germans had a feeling that September 9th could be the last day of the Rising, and they wanted to skillfully "play it out." The first proposals in this matter were put forward on August 18. As Stanisław Płoski writes, the Polish command was afraid that the Germans would eventually cut off the northern city center from the southern one. The northern city center would then have no chance of holding on, surrounded by the Germans on all sides. The Home Army Command no longer saw a chance for victory; however, the insurgent parliament - Council of National Unity (Polish: Rada Jedności Narodowej) - on the 8th of September, advocated for the need to stop the fight. Talks with General Rohr were undertaken on the basis of the decision of General Tadeusz Komorowski "Bór " in agreement with the government delegate Stanisław Jankowski, but contrary to some of the officers of his staff, openly opposing it. General Rohr had already announced that the Germans accept the Polish condition of granting veterans rights to prisoners of war from the Home Army.

The situation, however, was dynamic: suddenly, the German advance along Aleje Jerozolimskie weakened, and at the same time, a dispatch arrived from London, which announced the imminent arrival of a great air-supply expedition to Warsaw to help the Rising. In addition, there was a resumption of fighting on the right bank of the Vistula River, which the next day, on the 10th of September, transformed into a regular attack of the First Belarusian Front headed in the direction of central Praga. With these signals, General ‘’Bór’’ decided to play for time. In the face of the already raging battles taking place in Warsaw’s Prague district, which in effect radically changed the situation. On the 11th of September, the negotiations were finally broken. Of course, it remains unclear how the transfer of Chopin’s heart, allegedly rescued by the German soldiers from the rubble of the Church of the Holy Cross, was supposed to influence the Polish decision. A few other questions come forward, the first one being, was it expected that Archbishop Szlagowski would show gratitude and join the negotiations? Was the mediation of the Polish church more widely counted on? Or was it supposed to create an atmosphere that would lead to an agreement, which was supposed to influence the emotions of the Poles (during this period, Germans viewed the Poles as stereotypically throughout history, as being a nation that made decisions under the direction of their emotions)? This is where the facts end, and what remains are only speculations. What also is left for speculation is the role of Priest Schulze, whose actions - in the opinion of Polish witnesses - led to a very positive result. At the same time, however, there are certain facts that reveal themselves within these accounts. Polish priests visited Shulze in Żyrardów, where he was stationed at the headquarters of the 9th Army, which operated there throughout the course of the Rising, directing the entire defense of the Vistula River line along its assigned section. In summary, it is certain that, fortunately, Frederic Chopin’s heart survived, and the Germans failed to exploit this situation for their propaganda.

Chopin’s heart remained in the care of Archbishop Szlagowski until the 17th of October of 1945, when, during the 96th anniversary of the composer’s death, the heart was taken to Żelazowa Wola, his birthplace, and from there it made its return to the Church of the Holy Cross located on the Krakowskie Przedmieście, which was slowly being reborn from the ruins.

Article by Paweł Brudek, PhD

Translated from Polish by Klaudia Szymonik

Bibliography/Sources

Literature Sources:

INTERNET SOURCES: